Difference between revisions of "Depth of Engagement"

(→Depth of Engagement) |

|||

| (14 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Whilst many of the examples of E-enabled systems found in the literature pay a great deal of attention to facilitating participants in the pursuit of meaningful dialogue around an area of shared significance, when we come to consider the reality of citizen participation in relation to policy- making, we must look through another lens as not all participation activities afford those participating a process that is open and transparent from beginning to end. | Whilst many of the examples of E-enabled systems found in the literature pay a great deal of attention to facilitating participants in the pursuit of meaningful dialogue around an area of shared significance, when we come to consider the reality of citizen participation in relation to policy- making, we must look through another lens as not all participation activities afford those participating a process that is open and transparent from beginning to end. | ||

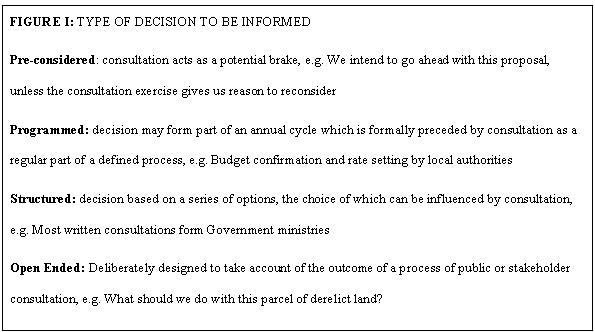

| − | In any public consultation, the general objective will be to inform some kind of decision, but the degree to which public participation is likely to have influence is largely dependent on the type of decision to be made. Jones and Gammell (2004) <ref> Jones R. and Gammell E. (2004), White Paper: Was it worth it?—evaluating public & stakeholder consultation- London: The Consultation Institute </ref> offer a classification of the types of decisions that public bodies open to consultation (see Figure below). | + | In any public consultation, the general objective will be to inform some kind of decision, but the degree to which public participation is likely to have influence is largely dependent on the type of decision to be made. Jones and Gammell (2004) <ref> Jones R. and Gammell E. (2004), White Paper: Was it worth it?—evaluating public & stakeholder consultation- London: The Consultation Institute </ref> offer a classification of the types of decisions that public bodies open to consultation (see Figure I below). |

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Typesofdecision1.JPG|thumbnail|630px|center|Figure I: Type of Decision to be Informed]] |

| + | |||

| + | Arnstein (1969)<ref name="arnstein"> Arnstein, S.R. July (1969) A Ladder of Citizen Participation. AIP Journal </ref> offers a useful typology for measuring the degrees of power and control between consulting public bodies and their citizenry deemed as ‘levels of participation’. Eight levels of participation are presented in a ladder formation with each rung corresponding to the level of influence that citizen participation can have on the outcome of a consultation process. The ladder illustrates participation as a rising scale with incremental levels of citizen empowerment in decision making ranging from cosmetic activities through to full citizen control of the decision- making /planning process. As the level of participation increases, so too does the transparency of the process and the potential for creativity in arriving at solutions. It demonstrates the variations in scope and effect that consultation and participation activities can have, with each position on the ladder presenting very different challenges and demands on the consulting organisations and participants alike. Morison (2004) <ref> Morison, J. (2004). Models of Democracy: from representation to participation? In: D. Oliver and J. Owell, eds, Changing Constitution. 1st edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 144-170 </ref>. has emphasised that care should be exercised in choosing which position to adopt. Not promising more than can be delivered is especially important given that the political context of public consultation places additional burdens of accountability on those responsible for conducting them. It can be argued that this accountability could be a limiting factor in terms of an authority’s willingness to embrace new and innovative methods. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Upon examination, the type of participation characterised by Arnstein (1969) <ref name="arnstein" /> may share a relationship with the type of decision to be informed and ultimately the choice of process to be adopted. Figure II (shown below) illustrates how the decision type restricts the potential for increased levels of participation. Decision types at the lowest level of the ladder have not been open to suggestion or deliberation by the public, but may be based on research and internal dialogue. In terms of depth of citizen engagement, at best they seek approval and at worst they are manipulation. Decisions of an open-ended nature are less evident in practice. Whilst the language deployed suggests a potential for a large degree of influence from citizens, delegated power and citizen control are rarely found in practice. (Click the figure shown below to enlarge it) | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Arnsteinladder.gif|thumbnail|630px|center|Figure II: A useful typology for measuring the degrees of power and control between consulting public bodies and their citizenry deemed as ‘levels of participation’]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [http://www.e-consultation.org/guide/index.php/Criteria_for_a_Demoractic_Process Criteria for a Democratic Process]<br> | ||

| + | [http://www.e-consultation.org/guide/index.php/Criteria_for_a_Deliberative_Process Criteria for a Deliberative Process] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 11:22, 21 May 2008

Depth of Engagement

Whilst many of the examples of E-enabled systems found in the literature pay a great deal of attention to facilitating participants in the pursuit of meaningful dialogue around an area of shared significance, when we come to consider the reality of citizen participation in relation to policy- making, we must look through another lens as not all participation activities afford those participating a process that is open and transparent from beginning to end.

In any public consultation, the general objective will be to inform some kind of decision, but the degree to which public participation is likely to have influence is largely dependent on the type of decision to be made. Jones and Gammell (2004) [1] offer a classification of the types of decisions that public bodies open to consultation (see Figure I below).

Arnstein (1969)[2] offers a useful typology for measuring the degrees of power and control between consulting public bodies and their citizenry deemed as ‘levels of participation’. Eight levels of participation are presented in a ladder formation with each rung corresponding to the level of influence that citizen participation can have on the outcome of a consultation process. The ladder illustrates participation as a rising scale with incremental levels of citizen empowerment in decision making ranging from cosmetic activities through to full citizen control of the decision- making /planning process. As the level of participation increases, so too does the transparency of the process and the potential for creativity in arriving at solutions. It demonstrates the variations in scope and effect that consultation and participation activities can have, with each position on the ladder presenting very different challenges and demands on the consulting organisations and participants alike. Morison (2004) [3]. has emphasised that care should be exercised in choosing which position to adopt. Not promising more than can be delivered is especially important given that the political context of public consultation places additional burdens of accountability on those responsible for conducting them. It can be argued that this accountability could be a limiting factor in terms of an authority’s willingness to embrace new and innovative methods.

Upon examination, the type of participation characterised by Arnstein (1969) [2] may share a relationship with the type of decision to be informed and ultimately the choice of process to be adopted. Figure II (shown below) illustrates how the decision type restricts the potential for increased levels of participation. Decision types at the lowest level of the ladder have not been open to suggestion or deliberation by the public, but may be based on research and internal dialogue. In terms of depth of citizen engagement, at best they seek approval and at worst they are manipulation. Decisions of an open-ended nature are less evident in practice. Whilst the language deployed suggests a potential for a large degree of influence from citizens, delegated power and citizen control are rarely found in practice. (Click the figure shown below to enlarge it)

Criteria for a Democratic Process

Criteria for a Deliberative Process

References

- ↑ Jones R. and Gammell E. (2004), White Paper: Was it worth it?—evaluating public & stakeholder consultation- London: The Consultation Institute

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Arnstein, S.R. July (1969) A Ladder of Citizen Participation. AIP Journal

- ↑ Morison, J. (2004). Models of Democracy: from representation to participation? In: D. Oliver and J. Owell, eds, Changing Constitution. 1st edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 144-170